يزداد أوضاع عمل الأطفال سوءًا في الفلبين، حيث أفاد مكتب الإحصاء الوطني الفلبيني في عام 2011 أن هناك 5.5 مليون طفل عامل في البلاد. يعمل 2.9 مليون منهم في الصناعات الخطرة مثل التعدين والمزارع. وأضافت الوكالة أن تسعمائة ألف طفل قد توقفوا عن الذهاب إلى المدرسة من أجل العمل.

تسلط هذه الأرقام المقلقة الضوء على الأوضاع السيئة التي يعاني منها العديد من الأطفال في الفلبين، الذين يفتقرون إلى الخدمات الاجتماعية الأساسية.

الفلبين إحدى الدول الموقعة على اتفاقية حقوق الطفل وغيرها من المعاهدات الدولية التي تهدف إلى تعزيز رفاهية الأطفال. وهناك أيضا المبادرة الشعبية لبناء الحكومة الصديقة للطفل، خاصة على المستوي المحلي. ولكن هذه القوانين والبرامج لم تنجح في القضاء على أشكال مختلفة من سوء المعاملة والفقر والحرمان التي يعاني منها العديد من الأطفال.

نشر معهد الكنسي في أبحاث التعلىم الفني (EILER)، الشهر الماضي، دراسة أكدت انتشار عمل الأطفال في المناجم والمزارع في مناطق مختلفة من البلاد. في مجتمعات المزارع، وحوالي 22.5 في المئة من الأسر لديها طفل عامل. وفي مدن التعدين، كان معدل عمالة الأطفال 14 في المئة.

يعمل الأطفال في حقول زيت النخيل كبائع الفاكهة أو في عملية الحصاد أو النقل، في حين يعمل الأطفال في مزارع قصب السكر في إزالة الأعشاب الضارة والحصاد وجلب المياه.

أما في المناجم فيعمل الأطفال عادة على جلب الماء، وحمل أكياس من الصخور، ويقومون بحمل قطع خشبية سميكة تستخدم لدعم الأنفاق تحت الأرض، ويصبح الأولاد عمال منتظمين في المنجم. وفي حالة عدم تمكن عمال المناجم الأساسيين من الحضور للعمل فهناك ما يسمي بالعامل الاحتياطي. تعمل الفتيات في المناجم بغسل الذهب أو تقديم الخدمات لعمال المناجم مثل غسل الملابس أو الطبخ.

رصد (EILER) أن الأطفال العاملين يتعرضون إلى ظروف جوية قاسية، وساعات عمل طويلة وبيئة صعبة أثناء استخدامهم لأدوات ومعدات دون المستوي المطلوب.

تلتقط الشاحنات الأطفال من منازلهم وتقوم بوضعهم في خيم بدائية تقع في محافظات مجاورة للمزارع، للإقامة والعمل لفترات تتراوح مدتها من أسبوعين إلى شهر بدون والديهم. ويتعرض الأطفال بشكل مباشر للمواد الكيميائية الضارة حيث أنها تستخدم في المزارع التي يعملون بها.

وعن الأطفال العاملين في المناجم، فهم يتعاملون مع أدوات خطيرة ويجبرون على العمل بدون معدات واقية لساعات طويلة. وهناك مخاطر اجتماعية مثل تعاطي المخدرات داخل الأنفاق، للحفاظ على الأطفال متيقظين لساعات طويلة، وأصبحت هذه سمة من سمات المناجم في البلاد.

شاركت الطفلة بيتانج، إحدى الأطفال العاملات في المزارع بمدينة مينداناو الفليبينية، تجربتها اثناء منتدى العام الأخير الذي نظمه EILER:

I was ten years old when I stopped going to school. I have lost hope that I might still go back to school, and I thought to myself that I would be a singer instead. I usually sing to endure and forget the feeling of pain and fatigue from working in plantation. It has been four years since I stopped schooling. I only reached the sixth grade level and then had to stop so I could work.

كنت في العاشرة من عمري عندما توقفت عن الذهاب إلى المدرسة. فقدت أمل الرجوع مرة أخري إلى المدرسة، وقلت لنفسي بأنني سأكون مغنية بدلًا من ذلك. وعادة ما أغني لكي أستطيع تحمل الشعور بالألم ونسيان تعب العمل في المزارع. اضطررت إلى التوقف عن الدراسة منذ أربع سنوات، بعد الوصول إلى الصف السادس حتى أتمكن من العمل.

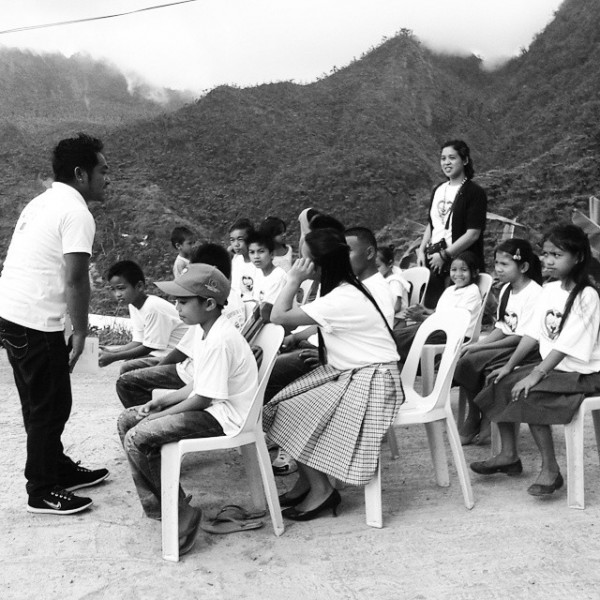

لحسن الحظ، هناك منظمات مثل EILER تناضل من أجل القضاء على أسوأ أشكال عمالة الأطفال في البلاد. أحد برامجها هو (العودة إلى المدرسة) Balik-Eskuwela الذييستهدف الأطفال العاملين. ويعتبر الاتحاد الأوروبي واحد من شركاء EILER على هذا المشروع.

Child labor exploitation is worsening in the Philippines. In 2011, the Philippine National Statistics Office reported that there were 5.5 million working children in the country, 2.9 million of whom were working in hazardous industries such as mining and plantations. The agency added that 900,000 children have stopped attending school in order to work.

Child labor exploitation is worsening in the Philippines. In 2011, the Philippine National Statistics Office reported that there were 5.5 million working children in the country, 2.9 million of whom were working in hazardous industries such as mining and plantations. The agency added that 900,000 children have stopped attending school in order to work.

These alarming numbers highlight the poor conditions experienced by many Filipino children, who lack key social services and access to welfare.

The Philippines is a signatory to the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other international instruments that aim to promote the welfare of children. There is also a popular initiative to build child-friendly government, especially at local level. But these laws and programs have not succeeded in eliminating the various forms of abuse, poverty and deprivation experienced by many children.

Last month, the Ecumenical Institute for Labor Education Research (EILER) published a baseline study which confirmed the prevalence of child labor in mines and plantations in various parts of the country. In plantation communities, about 22.5 percent of households have child workers. In mining towns, child labor incidence was 14 percent.

Child laborers in oil palm fields often serve as fruiters, harvesters, haulers, loaders, and uprooters. Meanwhile, child labourers in sugarcane estates work weeding, harvesting and fetching water.

In mines, child labourers usually fetch water, carry sacks of rocks, load the thick logs used to support the underground tunnels, or become errand boys for regular workers. They are also reserve workers and ‘relievers’, whenever regular miners cannot come to work. Girls in mines work in gold panning or providing services to miners such as doing their laundry or cooking meals.

EILER observed that child workers are exposed to extreme weather conditions, long working hours and a difficult environment while using substandard tools and equipment.

In plantations, trucks pick children up from their homes and bring them to makeshift tents located in nearby provinces to stay and work for periods lasting from two weeks to a month without their parents. Since most plantations use harmful agro-chemicals, the children working on them are directly exposed to these threats.

Their counterparts working in mines, meanwhile, are handling dangerous tools and are made to work without protective equipment for long hours. Social hazards such as the use of illegal drugs to keep children inside the tunnels awake for hours are also a regular feature of the country's mines.

Pitang holding a placard which reads: “I am a child labourer”. Photo from the Facebook page of Jhona Ignilan Stokes

A former child worker from Mindanao, Pitang, shares her experience in the plantations during a recent public forum organized by EILER:

I was ten years old when I stopped going to school. I have lost hope that I might still go back to school, and I thought to myself that I would be a singer instead. I usually sing to endure and forget the feeling of pain and fatigue from working in plantation. It has been four years since I stopped schooling. I only reached the sixth grade level and then had to stop so I could work.

Fortunately, there are groups like EILER which are campaigning for the elimination of the worst forms of child labor in the country. One of their programs is Balik-Eskuwela (Return to School) which seeks to bring child workers back to school. The European Union is one of EILER's partners on this project.